Roger Smith & the GREAT Britain Watch

The first time I met Roger Smith was in Manchester in the early 2000s. I’d travelled there from London specially to hear a talk he was giving at his horological alma mater. Being a poor young chap, I had to endure a number of privations to make this journey, but it was worth every hardship. Roger had his audience transfixed by descriptions of the various pocket watches he’d made, the small series of wrist watches for Theo Fennell, and his work with George Daniels and the ‘Millennium Watches’. He also described his horological training at that college; I had recently signed up to the same course at a different venue, and was eager to see the tantalising possibilities this path might offer.

Little did I know that my colleagues and I would one day work with Roger to curate his most salient masterpiece, ‘The GREAT Britain’ watch. This superb hand-made watch is a gift to the British nation to help showcase the many unique and wonderful talents that Britain has to offer. When the watch is not away being photographed or on tour around the world, it is kept at Watch Club for curating and safe-keeping.

We were delighted when the GREAT Britain campaign organisers approached us with the prospect of curating The GREAT Britain watch. We feel sure our decades of unblemished participation in the field of important watches, and our unique blend of skills led to Watch Club being appointed in this way.

Engine-Turning

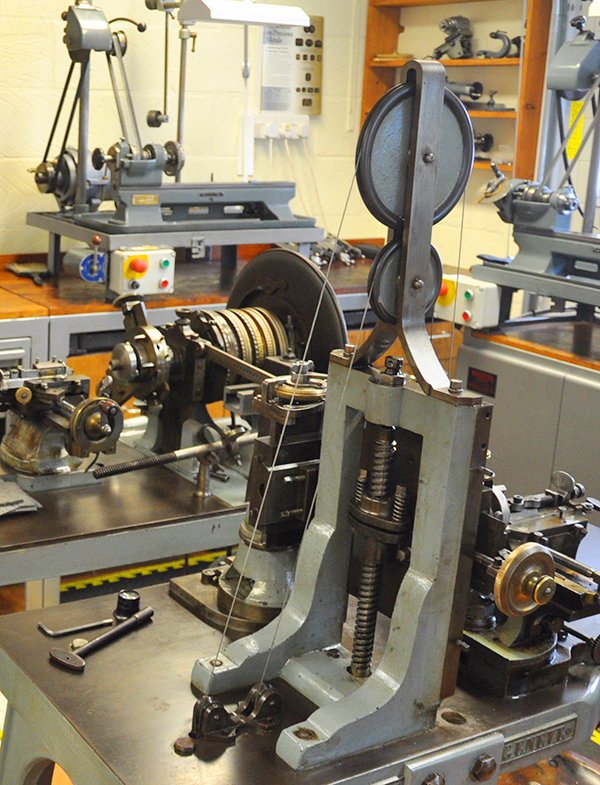

The GREAT Britain watch is unique in so many ways, not least of which is its exquisite Union Jack dial. Roger made the dial using the engine-turning machines he inherited from his master, George Daniels. Many of his machines are important artefacts in their own right, because George in turn procured them from Professor Torrens, who taught Daniels much of what he knew about watchmaking.

Roger’s engine-turning is arguably among the best to be found anywhere, but with The GREAT Britain, he has managed to take it to a completely new level. There is no other piece of guilloché quite like it. It began with three slices of sterling silver, patterned with wave, barleycorn and basketweave, the three most classical guilloché effects.

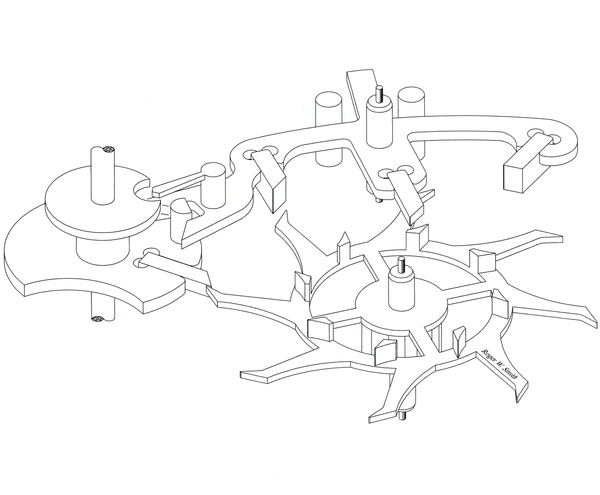

But this detailed profiling can never be carved fully where there are steps or internal corners. Roger instead proceeded to carve it up into the 34 individual pieces that make up the flag design so that he could assemble it from its constituent parts.

Then came the terrifying many-stage process of silver-soldering them together. The solder flows just a few degrees below the parent metal’s melting point. A single wave of the flame might render three months’ craft into a puddle of molten silver. But Roger’s skill and patience are more than a match for such things, as the finished product attests.

The next step was no less precarious. The pure powder-whiteness of the finished dial is attained by repeatedly re-firing and quenching in acid. Impurities in the surface are burned away at red heat, while the acid pickles away their coloured oxides.

Strength and Rigidity

• All flat steel, like this setting-lever spring, is at least 0.5mm thick

The beautifully blued steel hands of course are Roger’s signature foliate-tipped style, paired with hand-polished and blued roman numerals whose bold style perfectly orbits the pitch-point between traditional and contemporary.

Turning the heavy platinum case over, one of the first things that struck me about the movement is how unafraid Roger is of solidity. Delicacy may have some aesthetic appeal, but it does nothing for longevity, as Roger himself muses: ‘Strength and rigidity are little-used words in watch making’. In the GREAT Britain watch, the movement is reassuringly sturdy, and all the flat steel work is half a millimetre thick at minimum.

Improving the Co-Axial Escapement

• Roger has improved the Daniels Co-Axial Escapement, making it lighter and more concentric.

Some parts absolutely do need to be light. For instance the Co-Axial escape wheel, which has to accelerate from stopped at every tick. Excess weight here can’t be tolerated. Where Daniels stacked two escape wheels together, Roger managed to carve them out of one piece, saving 23% of the wheel’s weight, bringing efficiency, more concentricity and longer life.

Black-Polishing

All the flat steel is black-polished using a traditional tin lap. In this type of black polishing, the work is made optically flat, and so perfectly smooth that any remaining surface imperfections are smaller than the wavelength of light.

Most unusually, the escapement cocks and jewel settings are of rose gold, and these are also black-polished, something that I can say from experience is a completely unforgiving task.

Hand-Engraving by Charles Scarr

High-grade British watches from the past 200 years were characterised by their restraint; what we now think of as decoration, like blue screws, gilded plates and black-polished steel, were originally functional, mostly to do with resistance to corrosion. Among their few truly decorative concessions was the foliate engraving of the movement.

Here again, Roger defers to history – the raised top plate and the balance cock are covered in a magnificent scrollwork forest by the English master engraver, Charlie Scarr.

At every turn, Roger Smith’s GREAT Britain watch, the result of two years’ work, presents collectors with a profound prospectus of real watchmaking. With all of his output sold years in advance, we doubly appreciate the sacrifice that Roger made by donating this important watch to posterity, and Watch Club treasures this opportunity to help preserve and foster this ancient yet dynamic art.

The British Council sponsored this short film about Roger Smith, Watch Club, and the GREAT Britain watch. Click here to view.

Credits: Justin Koullapis